Touching Astroturf

My hair is never quite right. The top is too poofy, the sideburns too scraggly. Between shavings, a patch of stray stubble above the bridge of my nose suggests a unibrow. Also, there are dark spots under my eyes, and a mole on my chin, and a deep red blob that randomly appears at my hairline for some reason having to do with blood vessels.

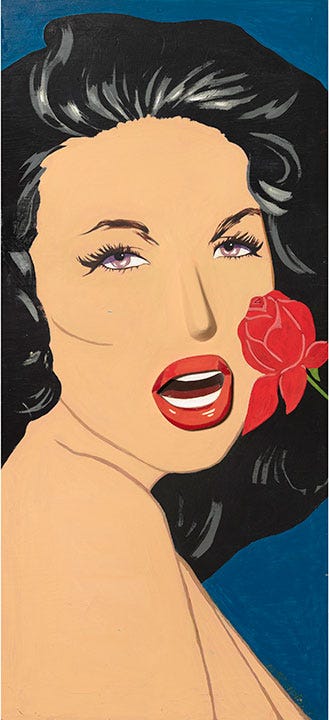

I have, in other words, a human head. It comes, as do almost all heads, with imperfections. Our hair is often out of place. Our faces are frequently unshaven. Our skin has “blemishes.” On one level, I know this. But on another level, I feel flawed—if not fundamentally, then for not spending enough time or money on styling my hair, or shaving every day, or skincare products. I know I’m not alone in this, obviously, or we wouldn’t have a multi-billion-dollar “beauty” industry. And I know I’m not saying anything terribly original when I blame the media—that is, the produced images we consume via television, film, and social media. But we (myself included) still haven’t truly reckoned with how insidious and pervasive these representations of reality are (even as social media has exponentially multiplied them).

In many ways, the jig is up. We all know, for example, that models in magazines have disorderly-eaten their way to an unhealthy weight, then been even more shaped and smoothed by Photoshop. Duh. We may have the same jaded perception of starlets on red carpets or Instagram influencers in front-facing videos. Our disbelief, though, is not boundless. Almost every single person we see on TV or in film has had their hair and makeup at least superficially done, and been professionally lit and filmed. Meanwhile, the number of produced images to which we are regularly exposed has exploded with the advent of streaming and smartphones. The human brain is no match for this onslaught. Philosopher Susan Bordo writes about the mismatch in her (iconic) 1993 book on women’s bodies, Unbearable Weight :

Sometimes, when I am analyzing and interpreting advertisements and commercials in class, students accuse me of a kind of paranoia about the significance of these representations as carriers and reproducers of culture. After all, they insist, these are just images, not “real life”; any fool knows that advertisers manipulate reality in the service of selling their products. I agree that on some level we “know” this. However, were it meaningful or usable knowledge, it is unlikely that we would be witnessing the current spread of diet and exercise mania across racial and ethnic groups, or the explosion of technologies aimed at bodily “correction” and “enhancement”…Like the knowledge of our own mortality when we are young and healthy, the knowledge that Cher’s physical appearance is fabricated is an empty abstraction; it simply does not compute. It is the created image that has the hold on our most vibrant, immediate sense of what is, of what matters, of what we must pursue for ourselves.

The “created image” has a hold on much more than our perceptions of our physical appearance. After all, these images show us not just the way people supposedly look, but also the homes we ostensibly live in and the interactions we ostensibly have, among other alleged aspects of the human experience. For instance: Nearly every home that appears in film or TV has been created by a set designer. These “manufactured homes” (to borrow a term) are often expensively decorated, and clean in the way only a home that’s regularly professionally cleaned can be, regardless of the income of the characters who live there. I clock this. I know that the real homes I go into run the gamut from Dwell-level cute to shabby-not-chic. But like Bordo says, this knowledge is “an empty abstraction”; I still feel like my own house isn’t stylish enough, or spotless enough. (I know I’m not alone in this, either, or else hosts wouldn’t apologize for “the mess” that’s nowhere to be seen.)

Similarly, viewers "know” that essentially every conversation that takes place on screen has been scripted (or edited) with the goal of efficiently moving plots or character development forward. And yet, it doesn’t seem like a coincidence that recent, more media-exposed generations appear to feel more often than their predecessors that interpersonal interactions are “awkward” (nor does it seem coincidental that these generations are more likely to experience social anxiety). When we feel like a situation is awkward, we’re comparing it unfavorably with a mental model of that situation. Despite our intellectual understanding that the conversations we’re consuming via media are crafted—fake—it’s these exchanges that are serving as those mental models, rather than real conversations improvised by living, breathing, sweating human beings.

There’s a one-paragraph short story by Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science,” in which the cartographers of an empire create a map so large and detailed that it actually covers the area it’s supposed to represent. Realizing how dumb that is, later generations let the map rot. The theorist Jean Baudrillard references this story in his essay “Simulacra and Simulations,” but argues that modern times have turned the tale on its head. “Henceforth…it is the map that engenders the territory,” he writes, “and if we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map.” I think he’s right: reality (the territory) is being gradually supplanted by representations of it (the map). Images are virtually as ubiquitous as their subjects, and they matter more. With even more immersive media, like the “metaverse,” on the way, there doesn’t seem to be a way out of this Black Mirror episode. “Touch grass” while you can; it’s getting re-sod with Astroturf.

JF